New York Times/Ismail Kadare Attributes His Writer’s Gift to His Mother

By

THE DOLL

By Ismail Kadare

The tribulation of a journey home prompted by the death of a parent is a subgenre of memoir driven by self-sympathy — understandable, if not always sufficient for the makings of good literature. The best in kind rely not just on the bidding of dusty memories, but also on the pursuit of new information: part remembrance, part detective story compelled by a sudden void that must be filled.

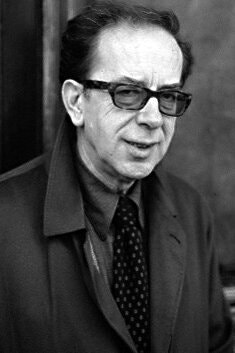

Ismail Kadare, the prolific Albanian novelist, is best known as an ironist who has earned comparisons to George Orwell and Milan Kundera, writing in the face of the ruthless Communist dictator Enver Hoxha, who ruled Albania from 1944 to 1985. By the early 1990s, though Hoxha was by then dead, Kadare had provoked enough ire within the regime to have to flee to Paris. He returned to his country only several years later, after receiving a call from his siblings informing him of the illness of his mother, whom he called the Doll. Such is the premise of Kadare’s autobiographical novel of the same title, originally published in Albanian in 2015 and now translated by John Hodgson into English.

The nickname contains a great deal of information about the narrator’s mother, or his childish perception of her, her fragility and what would “later strike me as her resemblance to paper,” he writes. There is the Kabuki-like mystery that the narrator, Ismail, finds inscribed in her face, an “unfounded naivety” and “extended adolescence,” all symptoms of a confined existence that he now understands was locked in place when she married at 17 and moved into the formidable, centuries-old home of her husband’s once well-to-do family, to reside under the imperious rule of her mother-in-law.

Some of the most pleasurable parts of “The Doll” arise from Kadare’s obvious thrill in revisiting Gjirokaster, the enchanting town of his birth, and reviving its interwar years, when the Doll was young. Political geography in Europe was in flux, but the customs of his mother’s life were still anchored, and vivid. The reader finds voyeuristic intrigue in the procession that accompanied her on her first post-nuptial visit home to her father, and in her mother-in-law’s announcement that, as a woman of a certain age, she would never again leave the house. A disruptive pressure on the Doll’s worldview comes in the form of a female cousin who chose to forgo marriage for a career in the increasingly darkening political nebula of Hoxha.

The novel also turns, partly, into a bildungsroman, as the narrator tries to tease out what it was about his mother’s sensibility that gave birth to “the writer’s gift” within him. Ismail becomes convinced that “everything that had harmed the Doll in life became useful to me in my art,” and that his mother had surrendered liberty in her own life “to give me all possible liberty as a human being, in a world where freedom was so rare and hard to find.”

Readers already familiar with Kadare’s writing will most likely find this delicate work of remembrance rewarding. Those who aren’t may struggle as the text tends toward the pat, with a feminist bent, though the narrator is less interested in politics than in hopping from place to place, character to character, imitating the pattern of the memories themselves as he takes us through his university days in Moscow and his break with family customs. But he declines to fill out the in-betweens. Kadare likens his project to a Russian poem in which the poet repeats the Russian word for “mother,” mat, three times, and on the fourth repetition leaves the word unfinished: matmatmatma. The final syllable — tma — means “darkness.” “An endless cycle of matma, ‘motherdarkness,’” Kadare writes, “in which both the mother and the darkness remain beyond understanding.”