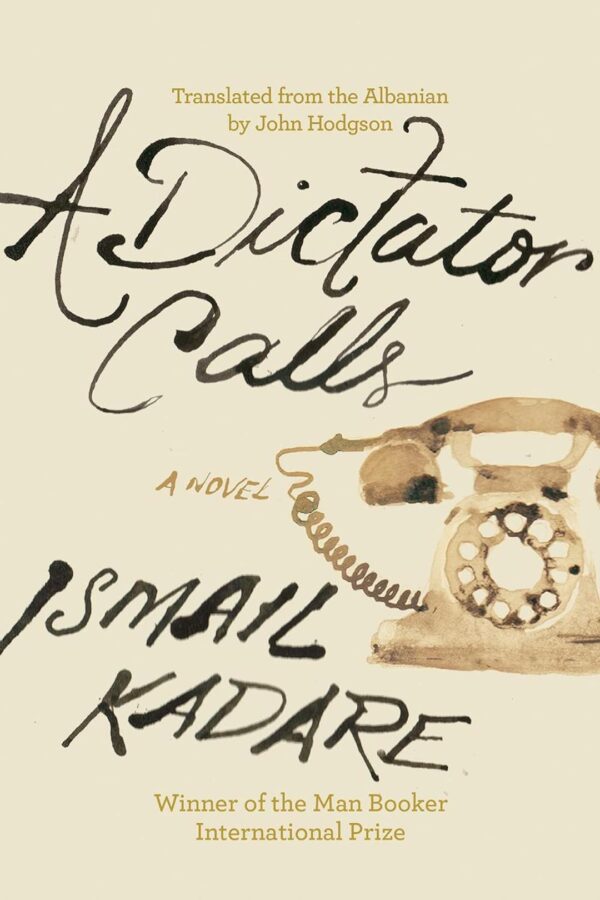

Dictator Calls by Ismael Kadare

A Dictator Calls melds history, fiction, memoir, and myth to explore the pernicious link between art and autocracy. Focused on Joseph Stalin’s alleged three-minute call to Boris Pasternak in 1934, Kadare’s persona, the “I” narrator, reveals his own quandary: how to make art, not propaganda, under a dictatorship. The three parts of this short text hopscotch through time and space—from 1935 to the present, from Paris to Moscow to Tirana—to portray the danger artists face under repressive regimes, where hearsay and innuendo may prove fatal. As Pasternak remarked when Osip Mandelstam began to read him an unpublished poem the rumor of which disturbed Stalin: “That’s not art, it’s suicide.” And so it proved for Mandelstam.

In part 1, Kadare explores his tie to Pasternak through dreams, memories, and his early Moscow novel, Twilight of the Eastern Gods, unpublished in Albania until 1978. Thus, when someone alludes to Pasternak’s infamous call, adding that Kadare received one as well, “from the big boss in Tirana . . . that Stalin of yours,” Kadare tells us that while his call was somehow congratulatory, Pasternak’s was later used to shame him. Given its thirteen credible versions, moreover, Kadare wonders what rumors exist about his own. He likewise admits that he juxtaposed himself to Pasternak in Twilight, which charts the latter’s fall from grace, his sudden transformation from Master-Poet to state enemy and public pariah, “darling of the bourgeois world,” after winning the Nobel Prize in 1958. Pasternak renounced the award, was moved from his dreary Moscow flat to a dacha in a writers’ community, but died two years later, becoming, per Kadare, “the first to be killed by a Nobel Prize.” When colleagues proposed that Kadare himself might make that list, he wondered which—the Nobel or the one for exile, prison, or death. In fact, he first made the former list in 1976 and was exiled to the interior later that year.

Part 2 foregrounds the call that featured Stalin, Pasternak, and mention of the towering but fearless, thus vulnerable, already-arrested Mandelstam (who succumbed to “typhus and hunger” two years later). Kadare remarks, “Two poets, one greater than the other. But only one tyrant . . . slaves of each other, in the same circle of Dante . . . torturing one another.” To strengthen his point, he offers historical precedents: Lenin’s apparent warmth toward the once-scorned Gorky (who must, he thinks, have harbored some threatening secret) and the tsar’s anger when Pushkin included his name, Aleksandr, in a manuscript, the search for that single word, and its deletion (except in a few originals).

Part 3 dissects the versions Kadare researched, all in some way documented, by KGB archives, Russian and Western scholars, mistresses, wives, and poet/critics. But together they seem to verify only when it happened, between whom, and for how long. Most accounts agree that Stalin hung up, displeased with Pasternak’s response to a question about Mandelstam, and that Pasternak tried to call back but was told that the line was created just for his call, evoking the Gate in Kafka’s Trial, which existed solely for the man seeking the Law, who never dared go through it: two mysterious byproducts of autocratic states.

Since no account proves definitive, Kadare writes, “Anybody . . . who thinks at first that thirteen versions are too many may, by the end of the case, think that these are insufficient!” Time erodes memory. Motives twist the narrative, including: envy and hatred—young Stalin published popular Georgian poetry, few possessed Pasternak’s talent, and literary would-be rivals (even, perhaps, Stalin) resented Pasternak’s role as Master-Poet, adored by the Russian people; ambition—the desire to curry favor with Pasternak or Stalin; fear and politics—Stalin, Pasternak, and their various cohorts might doctor accounts as politics dictated, and the KGB might fabricate or embroider to achieve strategic ends. But for Kadare, the call symbolizes “the mystery surrounding the tyrant and the poet . . . one we all share in . . . not to mention myself.” Indeed, Kadare’s art has long imaged such inscrutable ambiguities. For in Albania, Russia, or any autocracy, “Things believable only in books and never in real life” become “things in real life that would not be believed in books.”

Finally, the distorting mirrors in A Dictator Calls, another of Kadare’s dark fun houses, nonetheless illuminate the plight of two artists within despotic states, where prince and poet battle for power and the public. “This phone call was so close to me,” Kadare notes. Indeed, Dictator exposes the tightrope he and Pasternak had to walk. Belonging to “the family of artists,” Kadare urges that all who acknowledge this situation “bear witness to it . . . because art, unlike a tyrant, receives no mercy, but only gives it.” (Editorial note: The Winter 2021 issue of WLT includes a cover feature devoted to Kadare as the winner of the 2020 Neustadt Prize.)

Michele Levy

North Carolina A&T State University