‘Literature is the most valuable thing in life’

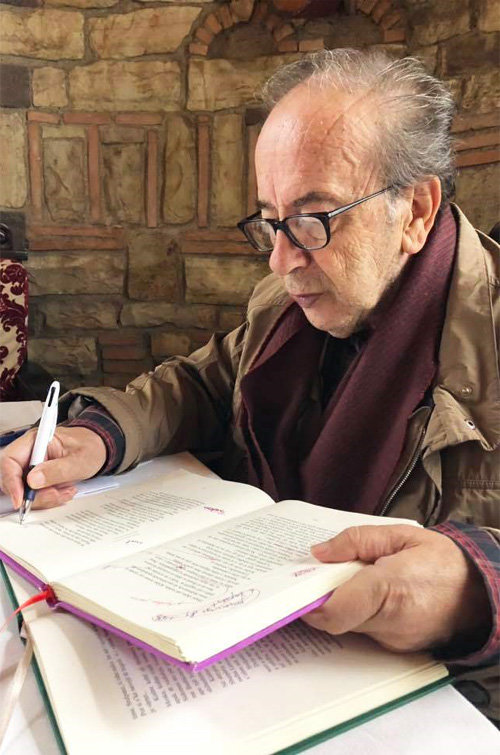

Albania, a small country in the Balkan Peninsula, fell into communism after the end of the World War ll. For decades, what people say and write about was strictly censored in communist Albania. Ismail Kadare, the winner of the 9th Park Kyung-ni Literature Award, was born in the country. The 83-year-old Albanian writer was deeply into literature as a teenager, transcribing Shakespeare’s Macbeth by hand and made a name for himself as a novelist in his 20s with his first novel “The General of the Dead Army (1963).” Kadare claimed political in France in 1990 and has continued to write there since then. “The world still doesn’t understand how tragic it is to live in a country that doesn’t want literature. Literature is the most valuable thing in life,” Kadare said in an email interview.

―What does it feel like to win the Park Kyung-ni Award?

“I’ve heard great things about the novelist Park Kyung-ni. I think it’s beautiful to have an award named after her. I feel even happier because my good friend Amos Oz was awarded the same award before. We all live under a gigantic roof called the earth. We all look different but love and respect one another. The same can be said of literature. It is universal and transcends time and space. I feel so happy to have the honor of winning the first international literature award in Korea.”

―Your first novel, “The General of the Dead Army,” was a huge sensation.

“The story came out from a small idea. Writers usually need to come up with interesting stories on their own but sometimes they come across a reality, which is like a present to them. I came across that reality in my country, which was politically unfortunate at that time. The novel is the story of a general from Italy, former enemy of Albania, charged with a humanitarian mission in Albania that was not used to the pains and a sense of guilty in the past. The deeper I delved into the theme, the more complicated I felt. It started as a short novel but was developed into a full-length novel.”

―You once said “The General of the Dead Army” is your most famous novel but not your best one.

“Yes, the novel received attention because I wrote it at the age of 25. I was born in a country whose political environment was extremely unreasonable. It was a hostile environment for those who were talented in literature. The novel was not a great start for me but it cast a meaningful question to Albania and to my journey as a writer.”

―You have criticized communism in your works, including “The Palace of Dreams (1981).”

“Yes, but I didn’t mean to make a mockery of the regime by using an inappropriate theme in my novel. Serious writers don’t want that to happen. Oppression was a theme that provided food for thought.”

―Although “The Palace of Dreams” was a fable, the Albanian regime noticed that it targeted them since it contained a detailed description of the capital Tirana.

“I thought the only way to raise the degree of completion was to provide vivid and detailed description of the situation. I believe it enlightened people about the greater truth. The novel gave me a lot of troubles. It was a kind of barrier in my journey as a writer. No other novels have yet been strictly investigated by socialists, critics, and communist regimes in quite the same way than this novel had been.”

―Have you been affected by any novels or writers?

“I’ve been affected by foreign novels. The case in point is Shakespeare’s works translated in Albanian. After reading “Macbeth,” everything else felt boring. I liked Greek author Homeros but not that much. If you find any humor in my novels, it’s all thanks to ‘Don Quixote’ by Cervantes.”

―Do you have any advice for prospective writers across the world?

“Publishing your book at a young age could be a disaster. If you become famous as a writer even before you become an accomplished writer, the pressure would make it hard for you to write. Sometimes I think publishing a book at such a young age should be prohibited like a ban on alcoholic drinks for the under-aged. My writings were once introduced in a newspaper even before I became a writer. In a column titled “Editor’s Mail,” they slammed my work as being written in a language that literature cannot accept.”

―You have a huge fan base in Korea as well.

“I feel thankful to have my works read in foreign countries, whether it be far away or close to home. That is what literature is about and it is based on cosmopolitanism. I want to thank Korean readers and my publisher for taking interest in my works.”

Seol Lee snow@donga.com

Ismail Kadare, intervistë ekskluzive për lexuesin koreano-jugor