The Nobel Prize in Literature 1991-2000

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1991

Nadine Gordimer “who through her magnificent epic writing has – in the words of Alfred Nobel – been of very great benefit to humanity”.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1992

Derek Walcott “for a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment”.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1993

Toni Morrison “who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality”.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1994

Kenzaburo Oe “who with poetic force creates an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today”.

Oe was born in 1935, in a village hemmed in by the forests of Shikoku, one of the four main islands of Japan. His family had lived in the village tradition for several hundred years, and no one in the Oe clan had ever left the village in the valley. Even after Japan embarked on modernization soon after the Meiji Restoration, and it became customary for young people in the provinces to leave their native place for Tokyo or the other large cities, the Oes remained in Ose-mura. Maps no longer show the small hamlet by name because it was annexed by a neighbouring town. The women of the Oe clan had long assumed the role of storytellers and had related the historical events of the region, including the two uprisings that occurred there before and after the Meiji Restoration. They also told of events closer in nature to legend than to history. These stories, of a unique cosmology and of the human condition therein, which Oe heard told since his infancy, left him with an indelible mark.

The Second World War broke out when Oe was six. Militaristic education extended to every nook and cranny of the country, the Emperor as both monarch and deity reigning over its politics and its culture. Young Oe, therefore, experienced the nation’s myth and history as well as those of the village tradition, and these dual experiences were often in conflict. Oe’s grandmother was a critical storyteller who defended the culture of the village, narrating to him humourously, but ever defiantly, anti-national stories. After his father’s death during the war, his mother took over his father’s role as educator. The books she bought him – The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Strange Adventures of Nils Holgersson – have left him with an impression he says ‘he will carry to the grave’.

Japan’s defeat in the war in 1945 brought enormous change, even to the remote forest village. In schools, children were taught democratic principles, replacing those of the absolutist Emperor system, and this education was all the more thorough, for the nation was then under the administration of American and other forces. Young Oe took democracy straight to his heart. So strong was his desire for democracy that he decided to leave for Tokyo; leave the village of his forefathers, the life they had lived and preserved, out of sheer belief that the city offered him an opportunity to knock on the door of democracy, the door that would lead him to a future of freedom on paths that stretched out to the world. Had it not been for the drastic change the nation underwent at this time, Oe, whose love of trees is one of his innate qualities, would have remained in his village as his forefathers had done, and tended to the forest as one of its guardians.

At the age of eighteen, Oe made his first long train trip to Tokyo, and in the following year enrolled in the Department of French Literature at Tokyo University where he received instruction under the tutelage of Professor Kazuo Watanabe, a specialist on Francois Rabelais. Rabelais’ image system of grotesque realism, to use Mikhail Bakhtin’s terminology, provided him with a methodology to positively and thoroughly reassess the myths and history of his native village in the valley.

Watanabe’s thoughts on humanism, which he arrived at from his study of the French Renaissance, helped shape Oe’s fundamental view of society and the human condition. An avid reader of contemporary French and American literature, Oe viewed the social condition of the metropolis in light of the works he read. Yet, he also endeavored to reorganize, under the light of Rabelais and humanism, his thoughts on what the women of the village had handed down to him, those stories that constituted his background. In this sense, he was again living another duality.

Oe started writing in 1957, while still a French literature student at the university. His works from 1957 through 1958 – from the short story, The Catch, which won him the Akutagawa Award, to his first novel, Bud-Nipping, Lamb Shooting* (1958) – depict the tragedy of war tearing asunder the idyllic life of a rural youth. In Lavish are the Dead (1957), a short story, and in The Youth Who Came Late* (1961), a novel, Oe portrayed student life in Tokyo, a city where the dark shadows of the U.S. occupation still remained. Apparent in these works are strong influences of Jean-Paul Sartre and other modern French writers.

Crisis struck Oe’s life and literature with the birth of his first son, Hikari. Hikari was born with a cranial deformity resulting in his becoming a mentally- handicapped person. Traumatic as the experience was for Oe, the crisis granted him a new lease on both his life and his literature. Overcoming the agony and determined to coexist with the child, Oe wrote A Personal Matter(1964), his penning of his pain in accepting the brain-damaged child into his life, and of how he arrived at his resolve to live with him. Through the catalytic medium of humanism, he conjoined his own fate of having to accept a handicapped child into the family with that of the stance one ought to take in contemporary society, and wrote Hiroshima Notes (1965), a long essay which describes the realities and thoughts of the A-bomb victims.

Following this, Oe deepened his interest in Okinawa, the southernmost group of islands in Japan. Before the Meiji Restoration, Okinawa was an independent country with its own culture. During World War II, the islands became the site of the only battle Japan fought on its own soil. After the war, the people of Okinawa were left to suffer a long U.S. military occupation. Oe’s interest in Okinawa was oriented, politically, toward the lives of the Okinawans living on what became a U.S. military base, and, culturally, to what Okinawa meant to him in terms of its traditions. The latter opened out to a broadened interest in the culture of South Koreans, enabling him to further appreciate the importance of Japan’s peripheral cultures, which differed from Tokyo-centered culture. This pursuit provided realistic substance to his study of Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory regarding a people’s culture which led him to write The Silent Cry (1967), a work that ties in the myths and history of the forest village with the contemporary age.

After The Silent Cry, two streams of thought, which at times flow as one, are apparent and consistent in Oe’s literary world. Starting with A Personal Matter is one group of works that depicts his life of coexistence with his mentally-handicapped son, Hikari. Teach Us to Outgrow our Madness (1969), a two-volume work, painfully portrays both the agony-laden trials and errors he experiences in his life with his yet unspeaking infant child, and his pursuit of his father he lost during the war. My Deluged Soul* (1973) depicts a father who relates to his infant child who, through the medium of the songs of the wild birds, has started to communicate with the family, and who empathizes with youths that belong to a belligerent and radical political party. Rouse Up, O, Young Men of the New Age!* (1983), a work in which Oe draws upon images from William Blake’s Prophecies, depicts his son Hikari’s development from a child to a young man, and thus crowns the works he wrote about his handicapped child.

The second group are stories in which Oe relates characters who he establishes in the theater of the myths and history of his native forest village, but who interact closely with life in today’s cities. This world of Oe’s fiction, starting with Bud- Nipping, Lamb-Shooting and followed by The Silent Cry, came to shape the core of his entire literature. Making full use of new ideas of cultural anthropology, these works represent the totality of Oe’s world of fiction, as evidenced in Letters to My Sweet Bygone Years (1987), a work about a young man who, banking on his cosmology and world-view of Dante, strives but fails to establish a politico- cultural base in the forest.Contemporary Games is a story that alternates between myth and history, which Oe supports with the matriarch and trickster principles he draws from cultural anthropology. He rewrote this work in narrative form as M/T and the Wonders of the Forest* (1986). With the aid of W.B. Yeat’s poetic metaphors, Oe embarked on writing The Flaming Green Tree*, a trilogy comprised of Until the ‘Savior’ Gets Socked* (1993), Vacillating* (1994), and On The Great Day* (1995). Oe has announced that with the completion of this trilogy, he will enter into his life’s final stage of study, in which he will attempt a new form of literature. The implication of this project is that Oe deems his effort at presenting his cosmology, history and folk legend as having been brought to full circle, and that he has succeeded in creating, through his portrayal of that place in the valley and its people, a model for this contemporary age. It also implies that he considers Hikari’s becoming a composer, in actuality, surpasses the importance of his own literature about him.

Oe’s winning the Nobel Prize for 1994 has thus encouraged him to embark on his pursuit of a new form of literature and a new life for himself.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1995

Seamus Heaney “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past”.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1996

Wislawa Szymborska “for poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality”.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1997

Dario Fo “who emulates the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden”.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1998

José Saramago who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality”.

——————————————————————————————————

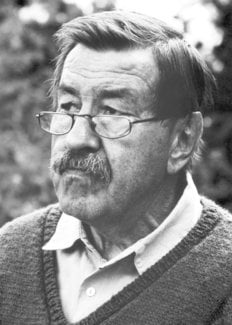

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1999

Günter Grass “whose frolicsome black fables portray the forgotten face of history”.

Grass was born in 1927 in Danzig-Langfuhr of Polish-German parents. After military service and captivity by American forces 1944-46, he worked as a farm labourer and miner and studied art in Düsseldorf and Berlin. 1956-59 he made his living as a sculptor, graphic artist and writer in Paris, and subsequently Berlin. In 1955 Grass became a member of the socially critical Gruppe 47 (later described with great warmth in The Meeting at Telgte), his first poetry was published in 1956 and his first play produced in 1957. His major international breakthrough came in 1959 with his allegorical and wide-ranging picaresque novel The Tin Drum (filmed by Schlöndorff), a satirical panorama of German reality during the first half of this century, which, with Cat and Mouse and Dog Years, was to form what is called the Danzig Trilogy.

In the 1960s Grass became active in politics, participating in election campaigns on behalf of the Social Democrat party and Willy Brandt. He dealt with the responsibility of intellectuals in Local Anaesthetic, From the Diary of a Snail and in his “German tragedy” The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising, and published political speeches and essays in which he advocated a Germany free from fanaticism and totalitarian ideologies. His childhood home, Danzig, and his broad and suggestive fabulations were to reappear in two successful novels criticising civilisation, The Flounder and The Rat, which reflect Grass’s commitment to the peace movement and the environmental movement. Vehement debate and criticism were aroused by his mammoth novel Ein weites Feld which is set in the DDR in the years of the collapse of communism and the fall of the Berlin wall. In My Centuryhe presents the history of the past century from a personal point of view, year by year. As a graphic artist, Grass has often been responsible for the covers and illustrations for his own works.

Grass was President of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin 1983-86, active within the German Authors’ Publishing Company and PEN. He has been awarded a large number of prizes, among them Preis der Gruppe 47 1958, “Le meilleur livre étranger” 1962, the Büchner Prize 1965, the Fontane Prize 1968, Premio Internazionale Mondello 1977, the Alexander-Majakowski Medal, Gdansk 1979, the Antonio Feltrinelli Prize 1982, Großer Literaturpreis der Bayerischen Akademie 1994. He has honorary doctorates from Kenyon College and the Universities of Harvard, Poznan and Gdansk.

| A selection of works by Günter Grass in English |

| The Tin Drum. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. London: Secker & Warburg, 1962. |

| Cat and Mouse. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1963. |

| Dog Years. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1965. |

| Four Plays. Introd. by Martin Esslin. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967. |

| Speak out! Speeches, Open Letters, Commentaries. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. London: Secker & Warburg, 1969. |

| Local Anaesthetic. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970. |

| From the Diary of a Snail. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973. |

| In the Egg and Other Poems. Transl. by Michael Hamburger and Christopher Middleton. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977. |

| The Meeting at Telgte. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981. |

| The Flounder. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978. |

| Headbirths, or, the Germans are Dying Out. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982. |

| The Rat. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987. |

| Show Your Tongue. Transl. by John E. Woods. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987. |

| Two States One Nation? Transl. by Krishna Winston with A.S. Wensinger. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990; London: Secker & Warburg. |

| The Call of the Toad. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992. |

| The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising. Transl. by Ralph Manheim. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1996. |

| My Century. Transl. by Michael Henry Heim. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999. |

| Too far afield. Transl. by Krishna Winston. London: Faber, 2000. |

Günter Grass died on 13 April 2015.

———————————————————————————————————

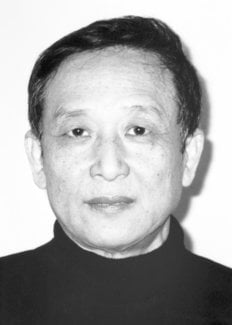

The Nobel Prize in Literature 2000

Gao Xingjian “for an æuvre of universal validity, bitter insights and linguistic ingenuity, which has opened new paths for the Chinese novel and drama”.

Xingjian, born January 4, 1940 in Ganzhou (Jiangxi province) in eastern China, is today a French citizen. Writer of prose, translator, dramatist, director, critic and artist. Gao Xingjian grew up during the aftermath of the Japanese invasion, his father was a bank official and his mother an amateur actress who stimulated the young Gao’s interest in the theatre and writing. He received his basic education in the schools of the People’s Republic and took a degree in French in 1962 at the Department of Foreign Languages in Beijing. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) he was sent to a re-education camp and felt it necessary to burn a suitcase full of manuscripts. Not until 1979 could he publish his work and travel abroad, to France and Italy. During the period 1980-87 he published short stories, essays and dramas in literary magazines in China and also four books: Premier essai sur les techniques du roman moderne/A Preliminary Discussion of the Art of Modern Fiction (1981) which gave rise to a violent polemic on “modernism”, the narrative A Pigeon Called Red Beak (1985), Collected Plays (1985) and In Search of a Modern Form of Dramatic Representation (1987). Several of his experimental and pioneering plays – inspired in part by Brecht, Artaud and Beckett – were produced at the Theatre of Popular Art in Beijing: his theatrical debut with Signal d’alarme/Signal Alarm (1982) was a tempestuous success, and the absurd drama which established his reputation Arrêt de bus/Bus Stop (1983) was condemned during the campaign against “intellectual pollution” (described by one eminent member of the party as the most pernicious piece of writing since the foundation of the People’s Republic); L’Homme sauvage/Wild Man (1985) also gave rise to heated domestic polemic and international attention.

In 1986 L’autre rive/The Other Shore was banned and since then none of his plays have been performed in China. In order to avoid harassment he undertook a ten-month walking-tour of the forest and mountain regions of Sichuan Province, tracing the course of the Yangzi river from its source to the coast. In 1987 he left China and settled down a year later in Paris as a political refugee. After the massacre on the Square of Heavenly Peace in 1989 he left the Chinese Communist Party. After publication of La fuite/Fugitives, which takes place against the background of this massacre, he was declared persona non grata by the regime and his works were banned. In the summer of 1982, Gao Xingjian had already started working on his prodigious novelLa Montagne de l’Âme/Soul Mountain, in which – by means of an odyssey in time and space through the Chinese countryside – he enacts an individual’s search for roots, inner peace and liberty. This is supplemented by the more autobiographical Le Livre d’un homme seul/One Man’s Bible.

A number of his works have been translated into various languages, and today several of his plays are being produced in various parts of the world. In Sweden he has been translated and introduced by Göran Malmqvist, and two of his plays (Summer Rain in Peking, Fugitives) have been performed at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm.

Gao Xingjian paints in ink and has had some thirty international exhibitions and provides the cover illustrations for his own books.

Awards: Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres 1992; Prix Communauté française de Belgique 1994 (for Le somnambule), Prix du Nouvel An chinois 1997 (for Soul Mountain).

| A selection of works by Gao Xingjian in English |

| Wild Man: a Contemporary Chinese Spoken Drama. Transl. and annotated by Bruno Roubicek. Asian Theatre Journal. Vol. 7, Nr 2. Fa1l 1990. |

| Fugitives. Transl. by Gregory B. Lee. In: Lee, Gregory B., Chinese Writing and Exile. Central Chinese Studies of the University of Chicago, 1993. |

| The Other Shore : Plays by Gao Xingjian. Transl. by Gilbert C.F. Fong. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1999. |

| Soul Mountain. Transl. by Mabel Lee. HarperCollins, 1999. |

| One Man’s Bible. Transl. by Mabel Lee. HarperCollins, 2002. |

| Contemporary Technique and National Character in Fiction. Transl. by Ng Mau-sang. [Extract from A Preliminary Discussion of the Art of Modern Fiction, 1981.] |

| “The Voice of the Individual”. Stockholm Journal of East Asian Studies 6, 1995. |

| “Without isms”. Transl. by W. Lau, D. Sauviat & M. Williams. Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia. Vols. 27 & 28, 1995-96. |